HEALTH INVESTIGATION: CEREBRAL PALSY: How Families, Experts Manage the Struggles

By Julius Nsikak

At just nine years old, God’spower Effiong lives with a reality most of his peers cannot imagine. Diagnosed with cerebral palsy shortly after birth, the condition has shaped his childhood, influencing his growth, speech, and ability to interact with others.

On a quiet afternoon in Uyo, he is seen trying to keep up with his siblings in their residential compound along Aka Etinan Road. His steps are unsteady, his movements painfully slow, and his words often melt into sounds only his closest relatives can interpret. Yet when he manages a smile, it speaks louder than any words he cannot say.

Family members recall how his late mother, Mrs Imaobong Inyangette, devoted herself to his care. Before her untimely passing, she made frequent visits to Nsit Ibom Medical Centre to collect vitamins and supplements for her son, determined to strengthen his fragile health.

“She never gave up on him,” his eldest sister said. “Even when she was tired, she would still look for ways to make him strong. She wanted him to live like other children.”

Despite her efforts, God’spower’s progress has been slow. He did not walk until after his second birthday, and even then, his legs appeared too thin for his frame. His buttocks are flattened, his movements restricted, and at nine years old, he weighs just 11 kilograms, far below the expected weight for his age.

UNDERSTANDING THE CONDITION

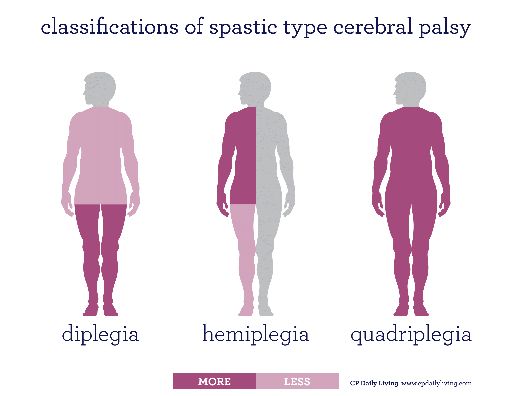

Cerebral palsy is not a single illness but a group of neurological disorders that affect movement, muscle tone, and posture. It is caused by abnormal brain development or brain damage occurring before, during, or shortly after birth.

At the University of Uyo Teaching Hospital (UUTH), one of the few tertiary health institutions in Akwa Ibom equipped to handle complex paediatric cases, Dr Nsisong Udoudo (FMCPaed), a consultant paediatric neurologist, offered crucial insights into the causes, management, and systemic gaps affecting families in Nigeria.

“Cerebral palsy,” she explained, “is not a single illness but a group of permanent disorders of movement and posture caused by non-progressive disturbances or injury to the developing foetal or infant brain. It is one of the most common motor disabilities that begins in childhood. These children typically show delays in motor development such as difficulty controlling the neck, sitting, crawling, or walking, as well as abnormal muscle tone, gait problems, and sometimes speech, feeding, or learning difficulties. The condition does not disappear in adulthood; rather, the affected child grows into an adult with cerebral palsy.”

Dr Udoudo identified several causes and risk factors, many of which are preventable with proper healthcare.

“Complications during labour, such as birth asphyxia, where the baby is unable to initiate or sustain breathing at birth are major causes,” she said. “Others include prematurity, very low birth weight, neonatal jaundice, and infections such as meningitis or sepsis. Maternal illnesses, poor antenatal attendance, and untreated infections also play significant roles. Unfortunately, poor access to good obstetric and neonatal care, and delays in recognising and managing complications, make the situation worse in Nigeria.”

According to her, the burden of cerebral palsy in Nigeria, and particularly in Akwa Ibom, is significant.

“Globally, the incidence is about 3.6 per 1,000 children, with a higher rate in low- and middle-income countries,” she noted, referencing data from the U.S. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “Here in Uyo, about three to four out of every ten children seen in our paediatric neurology clinic at UUTH are living with cerebral palsy.”

When asked about early detection, Dr Udoudo explained that diagnosis can often be made between 18 and 24 months of age.

“Parents and caregivers should watch for warning signs such as poor head control, floppy or unusually stiff muscles, delayed sitting or walking, feeding difficulties, or persistent primitive reflexes,” she advised. “Any baby who experiences a difficult delivery, prematurity, jaundice, or seizures at birth should be closely monitored.”

While there is no cure for cerebral palsy, Dr Udoudo emphasised that it can be managed effectively through multidisciplinary care.

“Management involves physiotherapy, occupational and speech therapy, orthotic support such as braces, nutritional management, spasticity control, and, in some cases, orthopaedic surgery,” she explained. “Children also need support for associated conditions like epilepsy, vision or hearing impairments, and feeding or speech difficulties.”

Beyond medicine, the consultant shed light on the emotional and financial strain families face.

“Caring for a child with cerebral palsy can be financially draining,” she admitted. “The cost of therapy, medications, and orthotic devices ranges from a few thousand to hundreds of thousands of naira, depending on the severity of the condition. The burden isn’t just financial, it’s emotional and psychological. Many parents battle anxiety, depression, and social isolation due to stigma.”

She further pointed out that physiotherapy, which plays a vital role in improving mobility and preventing deformities, remains out of reach for many.

“Physiotherapy helps prevent contractures and trains families on home-based exercises, but cost and access remain huge challenges. Here at UUTH, our clinic only holds once a week, every Tuesday. We simply do not have enough staff to run more sessions.”

Comparing Nigeria’s situation to global standards, Dr Udoudo said that while teaching hospitals offer relatively good multidisciplinary care, coverage remains grossly inadequate. “There are too few specialists, limited rehabilitation equipment, and irregular funding. Families often travel long distances just to access care. In addition, disability and rehabilitation have not been given the political priority they deserve.”

On government policy, her response was blunt: “To the best of my knowledge, there are no specific government social support programmes for children with cerebral palsy. Most families depend on NGOs and community groups for help.”

She added that inclusive education is also lacking. “Sadly, most schools are not inclusive,” she said. “They lack ramps, accessible toilets, or adapted learning materials. Inclusive education is almost non-existent for children with severe disabilities.”

Dr Udoudo urged the government and policymakers to prioritise prevention and inclusion.

“We must strengthen maternal and newborn care to reduce preventable causes of cerebral palsy. Subsidising the cost of care, enforcing inclusive education, and funding hospitals adequately will make a real difference.”

Her final appeal was both urgent and heartfelt:

“We need stronger public awareness and education to reduce stigma and promote early intervention. Above all, we need funding for training, for equipment, and for families who have been left to struggle alone.”

Dr Godwin Noah, Medical Superintendent of the General Hospital, Ikono Local Government Area, stated that families and society play pivotal roles in prevention and management, roles that, according to him, “can never be overemphasised.”

“There are predisposing factors to the development of cerebral palsy, and reducing these can greatly minimise the risk,” he said. “Some include low birth weight, multiple pregnancies, prematurity, prolonged or obstructed labour, foetal distress, pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes, and neonatal infections like rubella. Families should encourage pregnant women to seek early antenatal care, embrace hospital delivery, maintain good nutrition, and avoid stigmatising children with cerebral palsy.”

Dr Aniefiok Udoh, another paediatric neurologist in Uyo, explained:

“Cerebral palsy does not progress like other diseases, but its effects last a lifetime. Children like God’spower need consistent therapies, physiotherapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy, and nutritional support. Unfortunately, many families in rural areas lack the resources to access such care.”

He added that while cerebral palsy cannot be cured, timely intervention can significantly improve mobility, communication, and quality of life.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), cerebral palsy is the most common motor disability in childhood, affecting an estimated one in every 500 children worldwide. Although non-progressive, its challenges last a lifetime, requiring ongoing support and inclusive care.

For God’spower, the challenges go far beyond medical struggles. His condition makes it difficult to learn at the same pace as his peers. Teachers often find it hard to engage him in class, and his limited responsiveness sometimes isolates him from other children.

“He is easily left out during play,” said his sister. “Some children laugh at him because he cannot run fast or talk clearly. It hurts us, but we keep encouraging him.”

The stigma attached to disability in some communities adds another layer of pain. Families often face whispers, pity, or outright neglect from neighbours and relatives. For many caregivers, the psychological and financial toll is overwhelming.

Across Nigeria, thousands of children live with cerebral palsy, yet awareness remains low. Many families resort to traditional remedies, spiritual interventions, or self-medication due to a lack of information or access to specialists.

Civil society organisations and NGOs occasionally step in with advocacy programmes, mobility aids, or free therapy sessions, but such interventions are few and far between. In Akwa Ibom, parents of children with special needs say government support is “minimal and inconsistent.”

Mr Iniobong Ekanem, a social worker, argued that inclusiveness remains the greatest gap.

“Children with cerebral palsy deserve to be in school, to play, and to be accepted. But the truth is, most schools are not equipped to handle their needs, and most communities do not understand their struggles.”

VOICES OF STRUGGLING FAMILIES

When you meet Mr Victor Tom, a quiet but determined father from Mkpat Enin Local Government Area, who lives with his family at No. 5 Mount Zion Avenue, Aka Etinan Road, Uyo, it doesn’t take long to see the weight of responsibility he carries. His nine-year-old daughter, God’sgrace, was born with a condition later diagnosed as cerebral palsy, a disorder that affects movement, muscle tone, and coordination.

“Right from birth, she couldn’t walk,” he began, his voice heavy with both love and fatigue. “But I never allowed that to stop her from going to school or living her life. I told myself that as long as I am alive, she must not be left behind.”

Born on September 2016, God’sgrace’s condition was noticed when she failed to meet early developmental milestones. At first, doctors reassured her parents that some children walk later. But as time passed, Victor’s concern deepened.

“My wife took her to the Cottage Hospital at Ukana Ikot Ibah,” he recalled. “They said she would eventually walk. Still, I knew something wasn’t right. Carrying her every day to school, watching her struggle to sit or hold things properly, it was painful. So I decided to take her to UUTH.”

Doctors later confirmed that her condition was linked to birth complications. “She didn’t cry when she was born,” Victor said. “And I was told that when a baby fails to cry immediately, oxygen doesn’t flow properly to the brain. That was what affected her.”

Though she cannot walk unaided and requires assistance for most physical activities, God’sgrace is remarkably intelligent. Now in Primary Four, she consistently performs at the top of her class. Teachers describe her as bright, articulate, and eager to learn despite her physical limitations.

But the journey has been financially and emotionally draining. “From day one, it has been a struggle,” Victor admitted. “We have spent everything, moving from one hospital to another, hoping she could walk. She is currently undergoing physiotherapy at UUTH, but it has not been easy.”

Victor lamented that the physiotherapy clinic operates only once a week. “I’ve pleaded for it to be increased to at least two days, but doctors said manpower cannot allow it. Many children are on the waiting list. Missing one session means waiting another week.”

He hopes one day his daughter will walk more independently. “They recommended a SEMA frame to support her movement,” he said. “If I can get that, it will help her learn to walk gradually.”

Despite everything, Victor remains optimistic. “I believe in technology,” he said. “If our medical systems were more technology-driven, many children like my daughter would have better chances. Machines can do what human strength cannot, but our hospitals need the equipment and trained personnel.”

THE ROLE OF GOVERNMENT

Government support for children with cerebral palsy is crucial, as the condition requires lifelong management, special care, and inclusive policies. Support should begin with healthcare, ensuring early diagnosis and intervention through free or subsidised screening for infants.

Rehabilitation centres should be established in state and local hospitals, equipped with physiotherapists, occupational therapists, neurologists, and speech therapists. Treatment costs, including therapy sessions, medications, assistive devices, and surgeries could be significantly reduced if covered under health insurance or government-funded programmes.

Education is another vital area. Children with cerebral palsy should not be denied access to learning. Governments must promote inclusive schools by training teachers to handle children with special needs, while ensuring facilities such as ramps, adapted toilets, wide doorways, and assistive technologies are available.

Beyond health and education, social protection is equally important. Parents and caregivers could benefit from free or subsidised training on how to manage cerebral palsy. Awareness programmes at community level would help combat stigma and discrimination.

These efforts must be backed by strong legal frameworks. Disability rights laws should be implemented and enforced to ensure access to healthcare, education, and equal opportunities. Representation of persons with disabilities and their caregivers in policymaking bodies would also give them a voice in decisions affecting their lives.

Government investment in research, data collection, and inclusive infrastructure would further help children like God’spower and God’sgrace not just to survive, but to thrive with dignity in a society that recognises their worth.