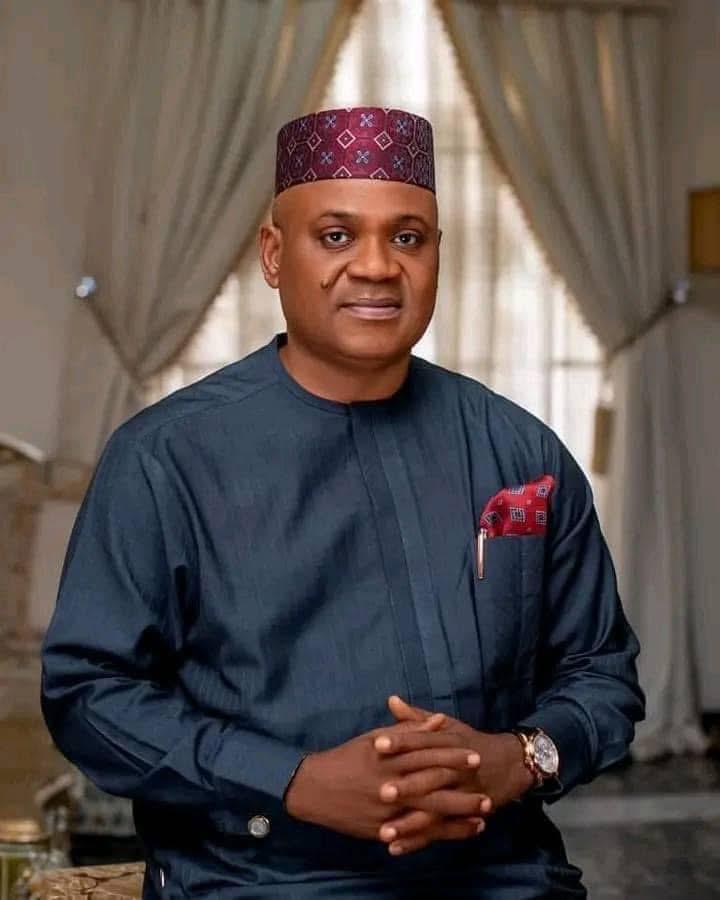

Cletus Ukpong, a Nigerian investigative journalist and Deputy Managing Editor of Premium Times, published a series of investigative reports on the rot in public education in Akwa Ibom State, and many people allegedly sponsored by the Akwa Ibom State Government went to Facebook and Twitter to attack him.

“These fellows deployed all kinds of derogatory words to insult me and my family online,” he said.

Ukpong is not alone. Eight among the 10 journalists in Akwa Ibom interviewed for this investigation reported

direct cases of digital surveillance, cyberbully, and coordinated online smear campaigns.

The two others said they know colleagues who were victims of such attacks.

In the Ukpong case, the majority of the people that harassed and intimidated him,

ironically, were fellow journalists allegedly hired by Akwa Ibom state government.

In Akwa Ibom, cyberbullying and other kinds of online harassment of news reporters are real. Increasingly, armies of trolls weaponise hate speech and online harassment against journalists, especially investigative reporters and women. UNICEF defined cyberbullying as the “intentional and repeated harm inflicted on someone through the internet, social media, texts and games using digital devices like cell phones and computers. It can involve name-calling, physical threats, spreading rumors and

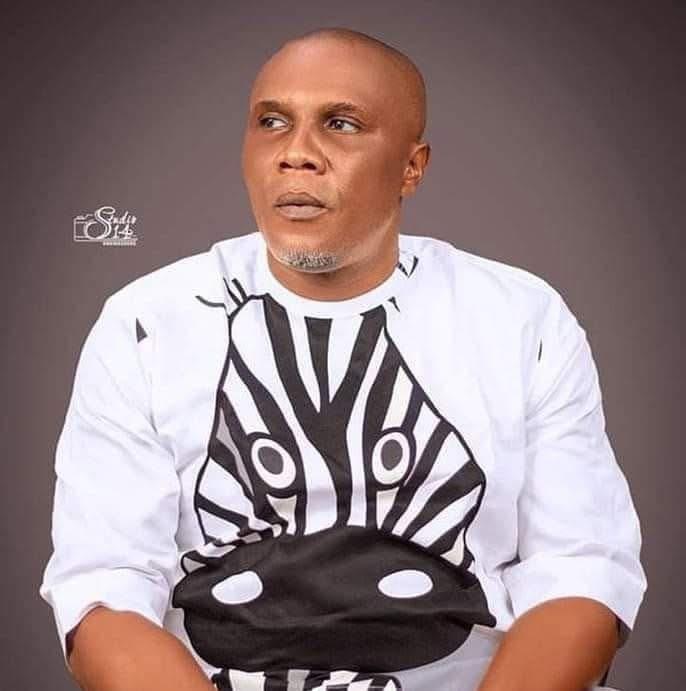

posting explicit pictures of someone online.” Ekemini Simon, an Uyo-based investigative journalist with Mail Newspaper, has been regular victim of name-calling online. Critics and online trolls have labelled him a mercenary sponsored to attack the state government in Akwa Ibom because of his several accountability reports exposing

wrongdoing and abuse of power in public office. In retaliation, pseudo accounts were created on social media and used to post false stories maligning him. But the public often comes to his defence, he said.

“Although I felt sad over the proliferation of the false narrative, the sadness wasn’t so deep

because I saw how many in the public often rose to my defense.”

Simon’s experience as well as that of other journalists has demonstrated a new form of

threats faced by journalists in the digital age.

A 2017 survey by the Council of Europe found that 40% of 940 journalists polled had been

subjected to harassment that affected their personal life, with 53% of cases consisting of

cyber harassment.

Women journalists are not exempted. They often are often targeted with sexist and racist

threats, including rape.

Mercy Obot, an Uyo-based female journalist with Crystal Express recalled the cyberattack she was exposed to for publishing an investigative story. The publication exposed

how social norms affect the rights of women in society.“ I was cyberbullied by men, especially on social media. This affected me personally, causing anxiety and stress. I became more cautious of my reportage on gender issues on

social media.”

Iniabasi Umo, a female journalist, the Akwa Ibom State Correspondent of Daily Trust hasnot directly experienced cyber attack, but whenever she reads some of the comments

about her report, she feels attacked indirectly. “But it didn’t discourage me professionally because I felt the negative comments were from a place of ignorance”. According to UNESCO, 73% of women journalists globally have experienced online violence, and one in five has reported being attacked or abused offline in connection with

threats received digitally, while 18% face threats of sexual violence.

Journalists in Nigeria have also reported increasing cases of digital surveillance, cyber

harassment, or orchestrated online smear campaigns, according to the Media Rights

Agenda (MRA).

Across Nigeria, those who dare to speak truth to power are increasingly becoming targets

of cyber attacks.

A 2021 report by the International Press Center on the “safety of journalists and

dimensions of press freedom violation” listed 57 cases of attacks and threats to 54

Nigerian male journalists and 3 female journalists and major newsrooms in Nigeria.

Reviewing Nigeria’s 2024 Press Freedom Index by Reporters Beyond Borders, BusinessDay

newspaper reported that Nigeria ranks 123 out of 180 countries, sliding three places from

the previous year. One of the key reasons cited was the rise in digital harassment and lack of legal

protections for journalists operating online.

Sharing a personal experience on cyberbullying, an investigative journalist, Ibanga Isine of Next Edition, reported a coordinated attempt by state actors to silence him.

“My phone has been hacked many times, and my conversations were eavesdropped by

state and political actors. It’s very frightening and frustrating and could make one reluctant

to embark on any serious investigation,” he told RSF. Isine said cyberbullying gets intensified because state and political actors do not want journalists to speak truth to power or the public to know what they are doing in secret,

especially as the internet has democratized information and communication.

“By keeping the public unaware of the reality of misgovernance and the associated impact,

political actors are able to perpetuate themselves in power,” he said

“These attacks are not merely digital annoyances; they are potent tools of suppression.

Weaponized misinformation, character assassination, and digital surveillance are modern

instruments of censorship that threaten the very foundation of democracy.”

Beyond the cyberspace, journalists have also been exposed to physical harassment, legal

torture and charges for daring to report truthfully and objectively.

An instance is the case of Tega Oghenedoro, a journalist with Secret Reporters, who was

detained by the Department of State Services (DSS) in Asaba, Delta State, following a story

he wrote about an alleged robbery incident in the Delta State Government House.

The detention, which followed summons for questioning, raised concerns about the

government’s tolerance for press freedom.

In another instance, two journalists, Joe Ogbodu and Prince Amour Udemude, were

remanded by a Magistrate Court in Asaba over a report published about the oil crisis in the

Uzere community.

Prince Amour Udemude and the Managing Editor of BIG PEN Nigeria Online Newspaper,

Joe Ogbodu were Sentenced in 2023 by the Magistrate Court in Asaba, to two years and

one year imprisonment, respectively with option of fine amounting to N100,000.00 and

N50,000.00, respectively.

These incidents further underscore the challenges journalists face in Nigeria, where

reporting the truth can lead to harassment, detention, or sometimes, death.

According to Azubuike Okey, the Akwa Ibom State correspondent of the News Agency of

Nigeria, the government and politically privileged class often resort to harassment of

journalists because they are insincere about governance, and have a lot to hide.

State and political actors do not want the public to know what they are doing, especially

now that the Internet has democratized information and communication, Isine added.

“It started with DSS and state governors acquiring sophisticated hacking devices and

capped with the enactment of section 24 of the Cybercrime Act which, before the last

amendment in 2024, made far-reaching provisions that criminalize the work of journalists

and whistleblowers.”

Recall that ECOWAS court had ruled that Nigeria’s section 24 of the 2015 Cybercrime Act

that criminalizes sending “offensive, insulting or annoying” online messages, was

inconsistent with human rights law.

The court in the ruling dated 25 May 2022 ordered the government to repeal the section,

citing incompatibility with the African Charter and International Covenant on Civil and

Political Rights.

That was necessary because journalists, whistleblowers, and activists were tried in court

for calling out corrupt officials and writing stories that expose wrongdoing”

Although 24 of the Principal Act, referring to the Cybercrimes (Prohibition, Prevention, etc.)

Act, 2015 was amended in 2024 to balance freedom of expression with public safety, the

amended law still contains serious ambiguity regarding what constitutes “false” or

“misleading” posts and “offensive online content.”

Dr. Abasiama Akpan, a cybersecurity expert and lecturer at the Federal University of

Technology, Ikot Abasi,, said this ambiguity often leads to misuse of the law, particularly by

politicians against journalists.

“There is a need for further clarification or definition of terms to prevent abuse,” he said.

Ukpong said persistent attacks on journalists can erode their courage to investigate

wrongdoing and hold those in power accountable.

“Professionally, I lost confidence in journalism in Akwa Ibom State because some of those

who attacked me online were journalists, editors, and newspaper publishers in the state.

“It is pretty difficult for journalists to hold the government and the powerful to account if

they lose the courage to investigate wrongdoing and official corruption. And of course

Nigeria’s democracy will be under threat, as it is right now. “

He urged citizens to speak up against attacks on journalists, and rally support for

journalists who face digital threats.

Why This Story Matters?

In today’s hyper-connected world, freedom of expression, access to information, and a free

press form the bedrock of democracy. But increasingly, these rights are under siege.

This erosion of press freedom in Akwa Ibom is a great concern for Egufe Yafugborhi, Akwa

Ibom State correspondent of Vanguard Newspaper.

“When journalists are silenced, democracy is weakened. When misinformation thrives, the

public is misled. And when digital attacks go unchecked, the price is not just paid by the

press; it is paid by society as a whole,” he said

In fact, Kufre Carta, a reporter in Uyo has started to wonder if investigating abuse of power

and wrongdoing in public office is actually worth the trouble.

He however added quickly that this kind of thought weakens the resolve of journalists to

hold power to account and urged them instead to fulfil their social contract to the people.

Cyberbullying as a new form of media censorship.

Hanson Johnson, CEO of Start Innovation Hub and a cybersecurity expert, provides a professional perspective on cyberbullying. Johnson said cyberbullying can have devastating effects on journalists, impacting them psychologically, emotionally, socially, academically, professionally, and physically.

“Victims [journalists] may experience depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, shame, fear,

isolation, anger, and frustration, Cyberbullying can also lead to PTSD, suicidal thoughts,

and physical symptoms like sleep disturbances and headaches,” he says.

Dr. Akpan urged journalists to prioritize their online safety to protect themselves and their

work. The way to do that is to regularly monitor their online presence, search for mentions of

themselves, and report harassment to platforms and authorities, and seek legal advice, he

said. He advised them to use strong, unique passwords and enable two-factor authentication to

prevent unauthorized access to their accounts. “Building support networks with colleagues, friends, and family is also essential for emotional support and guidance. Government spokesmen advocate credible journalism as antidote for cyberbullying harassments.

When questioned about the harassment of journalists in the state over critical reporting, Akwa Ibom state’s commissioner for information, Aniekan Umanah denied his involvement

in such an act against journalists. He, however, urged journalists to prioritize professionalism to avoid litigation and

harassment. “Journalists should stay factual and avoid sensationalism. With the rise of digital media,

fact-checking and verification are crucial.”

Umanah’s colleague, Ernest Akpan, the special adviser to the Akwa Ibom state governor on Local Media, toe the same official line of advising journalists, emphasizing the importance

of constructive criticism and fact-checking in journalism.

Ndueso, who was a media aide to former governor Godswill Akpabio, said he valued his

journalist colleagues, and only responded when reports were inaccurate or malicious.

When asked how he handles criticism from journalists without political interests, Ndueso

said he provides feedback to the governor when reports are true and constructive.

“Sometimes these criticisms are made in a way that seems to incite public unrest against

the government. I recall correcting misinformation about the state’s COVID-19

preparedness, only to be personally attacked online by fellow journalists.

“I have control over a large number of media down-liners, I could have mobilized them to

go after my colleagues, I have what it takes, but I can tell you for free that I can never do

such a thing, but those are the things I am easily accused of doing.”

He said his commitment is to the success of the government by distinguishing between

constructive criticism and malicious attacks.

Mobilizing for Media Freedom

Experts believe that a multi-pronged approach is needed to stem the tide of cyber attacks

on journalists. First, they suggested the need for legal reforms, especially the ambiguous provisions of

section 24 of the 2024 Cybercrime act as amended..

Barr. Clifford Thomas, Executive Director, Foundation for Civic Education, Human Rights

and Developing Advancements, recommended an update on cybercrime laws to include

specific provisions against cyberbullying, doxing, and digital surveillance especially when

targeted at journalists. He also believes holding perpetrators accountable is key.

“The primary beneficiary of the bullying should be responsible for the consequences.

Cyberbullying is a criminal offense in Nigeria, punishable by imprisonment.” He said

To protect journalists, Akwa Ibom State Director, Center for Human Rights and

Accountability Network (CRAN), Otuekong Franklin Isong suggests civic education,

advocacy, and condemnation of cyberbullying.

“NGOs and civil liberty organizations should push for free access to information and

enforcement of the Freedom of Information Act”.

Herbert Batta, Professor of Science Communication and Media Studies at the University of

Uyo, considers online harassment of journalists as cyberbullying which is a crime under

the Nigerian law.

“When journalists are doing their jobs professionally and are cyberbullied, it’s their

responsibility to fight back through professional and legal means,” he said.

In a survey, UNESCO advised that digital literacy should be encouraged to empower the

public to recognize disinformation and understand the role of the media in democracy.

Newsrooms were urged to invest in cybersecurity training, encrypted communication

tools, and rapid-response protocols for journalists, among other interventions.

“Cyberbullying against journalists can have significant effects on democracy, including

chilling free speech and press freedom, limiting diversity of voices, and eroding trust in

media,” Dr Akpan said.

Experts have therefore canvassed for stakeholders support for the defense of press

freedom.

Organizations like CPJ, RSF, Free Press Unlimited, and Amnesty International work with civil

society to defend journalists and activists facing attacks.

In West Africa, CENOZO in Burkina Faso and Whistleblowers and Journalists Safety

International Centre in Ghana provide shelter for journalists fleeing attacks.

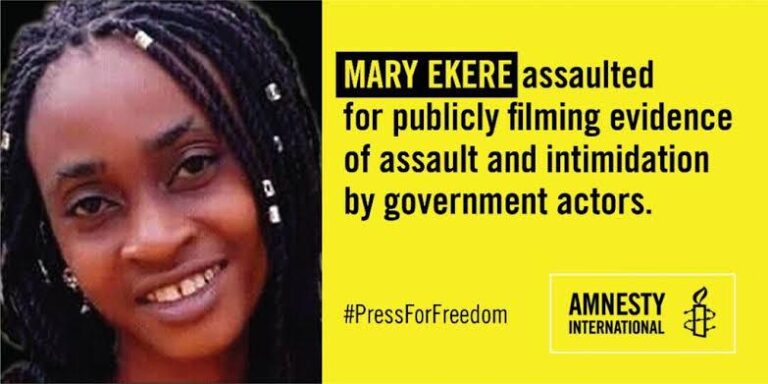

When Mary Ekere, an Uyo based female journalist was arrested, detained and cyberbullied in 2019 , organizations like the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) and the International Press Institute (IPI) provided her support.

The Nigeria Union of Journalists and the Nigeria Association of Women Journalists also

came to her rescue. But Ukpong wasn’t that lucky.

“I felt so unappreciated, so betrayed because I knew those reports were for the common

good,” he said.

This report is supported by the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) as

part of a project documenting issues focused on press freedom in Nigeria

Culled from Independent News Paper